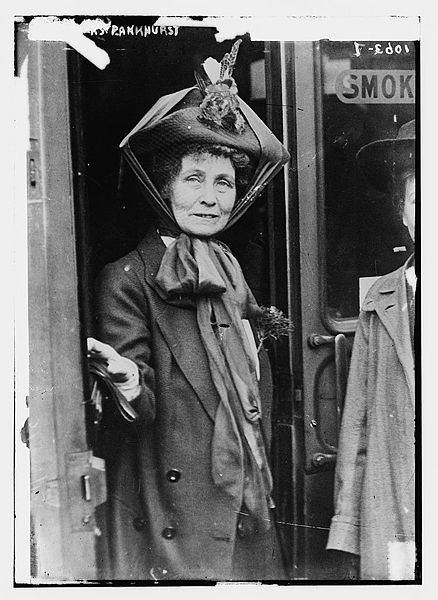

Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst (née Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was a political activist and leader of the British  suffragette movement. Although she was widely criticised for her militant tactics, her work is recognised as a crucial element in achieving women’s suffrage in Gender Equality in the Gender Equality in the United Kingdom.

suffragette movement. Although she was widely criticised for her militant tactics, her work is recognised as a crucial element in achieving women’s suffrage in Gender Equality in the Gender Equality in the United Kingdom.

Early Life and Education

Born in Manchester, Emmeline Pankhurst’s family were political and encouraged her interest in social activism from a young age. However, despite the parents’ progressive views, she did not receive the same education as her brothers since it was expected that she would marry. At the age of 15, she went to Paris to attend the École Normale de Neuilly. The school provided its female students with classes in chemistry and bookkeeping, in addition to traditionally feminine arts such as embroidery.

She returned to Manchester and at the age of 20, met and began a courtship with Richard Pankhurst, a barrister who had advocated women’s suffrage – and other causes, including freedom of speech and education reform. They were wed in Eccles on 18 December 1879.

Political Activism

During the 1880s, Pankhurst involved herself with the Women’s Suffrage Society. Pankhurst made their Russell Square home into a centre for political meetings and social gatherings, attracting activists of many types. The Pankhursts hosted a variety of guests including U.S. abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, Indian MP Dadabhai Naoroji, socialist activists Herbert Burrows and Annie Besant, and French anarchist Louise Michel.

In 1888 Britain’s first nationwide coalition of groups advocating women’s right to vote, the National Society for Women’s Suffrage (NSWS), split after a majority of members decided to accept organisations affiliated with political parties. ome of the group’s leaders, including Lydia Becker and Fawcett Society , created an alternative organisation committed to the “old rules”, called the Great College Street Society. Pankhurst aligned herself with the “new rules” group, which became known as the Parliament Street Society (PSS). When the reluctance within the PSS to advocate on behalf of married women became clear, Pankhurst and her husband helped organise another new group dedicated to voting rights for all women – married and unmarried.

The inaugural meeting of the Women’s Franchise League (WFL) was held on 25 July 1889 at the Pankhurst home in Russell Square. Early members of the WFL included Josephine Butler, leader of the Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts; Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy; and Harriot Eaton Stanton Blatch, daughter of US suffragist Susan B. Anthony .The WFL was considered a radical organisation, since i it supported equal rights for women in the areas of divorce and inheritance. It also advocated trade unionism and sought alliances with socialist organisations. The group’s radicalism caused some members to leave and the WFL fell apart one year later.

Women’s Social and Political Union

After the death of her husband, Pankhurst with colleagues founded in 1903 the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), an organisation open only to women and focused on direct action to win the vote. Three of her daughters joined her in the campaign; all three went to prison during protests. Pankhurst saw imprisonment as a means to publicise the urgency of women’s suffrage; in June 1909 she struck a police officer twice in the face to ensure she would be arrested. Pankhurst was arrested seven times before women’s suffrage was approved. The WSPU engaged in more militant measures as a means to attract attention including hunger strikes. Prison authorities frequently force-fed the women, using tubes inserted through the nose or mouth.

Press coverage was mixed; many journalists noted that crowds of women responded positively to speeches by Pankhurst, while others condemned her radical approach to the issue. In 1906 Daily Mail journalist Charles Hands referred to militant women using the diminutive term “suffragette” (rather than the standard “suffragist”). Pankhurst and her allies seized the term as their own, and used it to differentiate themselves from moderate groups.

Her reputation as a powerful speaker of women’s rights led to her visits of Russia, the United States and Canada. Upon the outbreak of WWI, she threw the WSPU in support of the government and ordered the suspension of the militant tactics of the WSPU. In 1918, women were granted the right to vote in Britain. By this time, the Pankhurst women’s politics differed significantly, with Pankhurst eventually joining the Conservative Party while Sylvia Pankhurst remained an anarchist.

Pankhurst died at the age of 70 in 1928 in Hamstead, London.

References