The gendered impact of armed conflicts

Article proposed and written by the Secretariat of the Euro-Mediterranean Women’s Foundation

Table of Contents:

- Introduction

- Countries in armed conflict and/or socio-political crisis with medium, high or very high levels of gender discrimination

- Gender and conflict: Peacebuilding

- Recommendations

- Conclusion

Introduction

War negatively affects every person, including men, women, and non-binary genders. Although we have access to only few sex-disaggregated data on the extent to which armed conflicts have repercussions on gender discriminations, it is possible to say that the short and long-term socio-economic effects of wars fall disproportionately on women. As evidenced by field data recently released by the United Nations (UN) Women about the ongoing Ukrainian crisis, 54% of people in need of assistance are women, and these numbers are expected to keep increasing. [i] Sima Bahous, Executive Director of the UN Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, explained during the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) meeting held on 11 April 2022 that increasing reports of rape and sexual violence committed against women in Ukraine – in the battlefield as well as in the massive displacement context – are raising “all the red flags” about a potential protection crisis. [ii]

As men represent most of the combatants, they suffer from direct violence, injuries, and killings in the battlefield. However, in modern wars civilians die to a larger extent than soldiers. Moreover, women are extremely impacted by wars in different ways: through systematic rape and sexual violence; greater levels of displacement and presence in refugee camps, where mortality rates tend to be higher; and social and economic vulnerability, due in large part to loss of access to sources of livelihoods and to basic services.[iii]

From the fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995 and UNSC Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) in 2000, to the adoption of UNSC Resolution 2467 on ending sexual violence in conflict in 2019 and the third EU Gender Action Plan (GAP III), women’s rights advocates have committed themselves for decades to place gender equality and women empowerment on top of the security agenda. The UN resolutions under the WPS agenda play an important role in framing women’s rights as critical components of international peace and security. They represent an essential framework for addressing the specific needs, rights and roles of women during conflict and for acknowledging the contribution of women to conflict resolution processes and the development of sustainable peace, while highlighting the necessity of involving them in conflict prevention, peacebuilding, and post-conflict reconstruction.[iv]

Since its creation in 2014, the Euro-Mediterranean Women Foundation (EMWF) – which has its Secretariat at the European Institute of the Mediterranean (IEMed) – has been collecting interesting reports, articles, and documents produced by a network of associations working on gender equality issues in the Euro-Mediterranean region. Based on these documents, this article aims – without wishing to be exhaustive – to analyse the issue of armed conflicts’ impact on gender, with a specific focus on Gender-Based Violence (GBV) during as well as in a post-war context. Furthermore, it will also address women’s inclusion within peacebuilding processes and its associated benefits. Finally, the article will present some specific recommendations to governments, policymakers, and civil societies in order to reduce the negative gender impacts of wars and armed conflicts. In fact, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s 2021 Working Paper on Gender Equality and Fragility, the amount of dedicated humanitarian, developmental, or peacekeeping/building resources that reach these fragile contexts where gender inequality is deeply rooted, is often inadequate. While it is clear that is essential to achieve gender equality within fragile contexts, resources must be appropriately mobilised to meet these needs. v

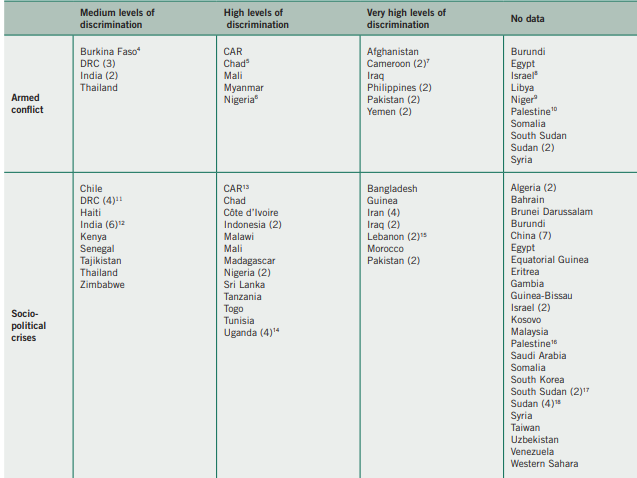

Figure 1: Countries in armed conflict and/or socio-political crisis with medium, high or very high levels of gender discrimination

Note: Table prepared based on levels of gender discrimination in the OECD’s Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) as indicated in the 2020 report vi and Escola de Cultura de Pau’s classifications of armed conflict and socio-political crisis. The SIGI establishes five levels of classification based on the degree of discrimination: very high, high, medium, low, and very low. The number of armed conflicts or socio-political crises in which the country is involved is given between parentheses. Source: Alert 2021! Report on conflicts, human rights and peacebuilding by Escola de Cultura Pau and Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.vii

As evidenced in the table above, data on gender discrimination levels in different states are not always available. However, from the figures shown in the table, we find that many countries where armed conflicts tend to occur more often than in others, have “high” and “very high” levels of gender discrimination– according to OECD’s SIGI indicators. viii The results of research in this field all point in the same direction: countries with high levels of gender inequality are more likely to be associated with both intrastate and interstate armed conflict, and peace established under more gender-equal conditions is more likely to hold. ix

The UN considers sexual violence related to conflicts to be “incidents or patterns of sexual violence […], that is, rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced pregnancies, forced sterilisation or any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity perpetrated against women, men, boys or girls.” x During armed conflicts, domestic violence against women is more frequent, it occurs even more often than sexual violence correlated to war. xi During the three years of war in Bosnia, 60,000 women suffered domestic violence, and 250,000 rapes were committed during the 100 days of genocide in Rwanda. xii According to the latest UN estimates on the issue, more than 60,000 women were raped during the civil war in Sierra Leone (1991-2022), more than 40,000 women in Liberia (1989-2003), and at least 200,000 in the Democratic Republic of Congo from 1998 to today. xiii For what concerns the current war in Ukraine, as specified by the 2019 United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) study xiv, 67% of women in Ukraine reported experiencing forms of violence since age 15, and one out of three Ukrainian women reported suffering from physical or sexual violence – before the outbreak of the conflict. According to UNFPA, the current crisis and displacement put these women at increased risk of sexual and physical violence and abuse. xv

Women also tend to be more affected than men by the negative consequences of the post-war period. In this context, rapes and GBV are still frequent. This occurs because, according to the Head of Research at the Institute for Inclusive Security, Marie O’Reilly, when soldiers trained in the use of force come back home in sexist and patriarchal contexts, they are faced with a transformation of gender roles – as women had to take control over the economic livelihood of the household in their absence – and are frustrated by the lack of work. xvi Moreover, women suffer more than men from the indirect consequences of wars. More than half of the cases of maternal death occur in fragile or conflict-destabilised nations. Furthermore, for women fleeing countries in conflict in search for a safe place, the nightmare continues in the refugee camps. Gauri Van Gulik, Amnesty International Deputy Director for Europe and Central Asia, acknowledged that many mistakes have been made in the past, from which it was possible to understand that women are at risk of suffering more assaults and sexual violence if institutions and organisations do not provide them with separated toilets and, in general, separated spaces in refugee camps. xvii

Gender and conflict: Peacebuilding

Women’s rights have been traditionally excluded from the security agenda. For example, sexual violence and intimate partner violence – which occur often in armed conflicts – have frequently been overlooked by security policies, even if we have seen a change of mentality towards a more gender egalitarian security agenda in recent years. However, women are still generally portrayed solely as victims, rather than active agents contributing to peace and reconciliation efforts or to peacebuilding in the aftermath of conflicts. xviii This is due to the persistent lack of female presence in places of power and in the decision-making processes at all levels, including in the security sector, in peace negotiations, and other conflict resolution activities. A gender-sensitive approach to security brings issues such as GBV and peacebuilding to the forefront of security policies, thus helping to develop a holistic vision of security. xix In fact, the European Union (EU) recently presented studies on the concrete efforts that women can bring into phases of peacebuilding, and the European Parliament adopted a resolution on this issue in October 2020 – within the framework of the GAP III – calling on the EU and its Member States to advance towards a “foreign and security policy that mainstreams a gender-transformative vision.” xx

The Security Council Resolution 1325 was the first landmark on the UN WPS agenda. It asks all parties involved in conflicts to increase the participation of women and to incorporate a gender perspective in all operations to protect peace and security. Approved in 2000, after many efforts and commitments of women’s right advocates, not much has changed since then. Today we still have few disaggregated data on female participation in peacebuilding processes. Moreover, the reality of facts – based on the data we have access to – is a lot less inclusive than what the UNSCR 1325 was advocating for: only two women had a role in conducting peace negotiations so far, and only one woman has signed peace agreements as chief negotiator, according to the Council of Foreign Relations. xxi Women are generally not included in peacebuilding processes, although it is recognised that peace made with female inclusion tends to last longer. xxii

In fact, from the analysis of 182 treaties signed between 1989 and 2011, it emerged that the peace processes that had seen the participation of women offered greater guarantees of duration: compared to those entrusted only to men, they had a 20% more chance of lasting at least two years, and 35% more chance of lasting over 15 years. xxiii Clare Castillejo, expert on gender, rights, and inclusion in fragile and conflict affected contexts, argues that this is due to the fact that women often manage to include some important issues in the peace agenda that men tend to neglect, such as inclusiveness and accessibility of women and vulnerable people to decision-making processes and institutions, as well as a gender equality perspective. xxiv In fact, as can be seen in the OECD’s 2020 States of Fragility Report, the limited participation of women in peace processes also reflects the lack of gender approach in peace agreements, since only a fifth of them refer to women. xxv

Recommendations

To reduce the war impacts on gender discrimination, collecting sex-disaggregated data is essential. It is in fact fundamental to globally acknowledge what we could see from the few data we have access to: that girls and women suffer from armed conflicts due to increased GBV, although at the same time that they can be drivers of change and strong supporters of a more lasting peace. To sustain their safe, meaningful, and inclusive participation in civic and public life, authorities, institutions, and policymakers must take into consideration the feedback of women and female civil society organisations. In general, these actors should:

- Strengthen women and girls’ access to education, information, and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) to ensure that every girl can succeed, despite circumstances resulting from conflict and political instability;

- Be aware of the positive role that girls, young women, and women have in achieving sustainable peace and social cohesion, giving therefore support to local girl- and women-led initiatives in the area of conflict prevention and peacebuilding;

- Participate in mandatory and tailored trainings on gender equality, especially useful for all managers of cooperation and humanitarian missions;

- Enhance their capacity to effectively prosecute and deliver reparations for conflict-related sexual violence, including for survivors in rural and peripheral areas;

- Continue expanding service coverage to ensure a holistic response to the issue of conflict-related sexual violence, including protection and security guarantees for victims, witnesses, and women’s human rights defenders;

- Enhance protection measures for people affected by, or at risk of, sexual violence and/or exploitation;

- Integrate a gender and intersectional perspective into all development aid external action activities;

- Include women from diverse backgrounds within the framework of policymaking and peacebuilding processes;

- Accompany the international frameworks that aim at incorporating the gender perspective in the security agenda, such as UNSCR 1325 and GAP III, with clear, measurable, time-bound indicators of success to monitor short-, medium- and long-term positive changes in this sense. xxvi

Conclusion

The elimination of the gender data gap has positive effects that go beyond the gender equality issue per se. Given the contribution that women are making in the most diverse fields, compensating for the data gap is beneficial for everyone. Too often, however, women are not allowed to contribute to solving the many global problems that we continue to believe are insoluble. Nevertheless, the data in our possession is unobjectionable: it is time that in building, designing, and developing the world we begin to take women’s lives and opinions into consideration.

Although it is true that too often women’s needs, experiences, opinions, and feedbacks have been neglected, many advances have been made towards gender equality in recent years. In fact, the political momentum to achieve a more equal and feminist society and institutions has not dissipated. As we can read in the OECD’s 2021 Working Paper on Gender Equality and Fragility, the global desire to effectively implement a more feminist security agenda remains strong, in line with the 20th anniversary of the UNSCR 1325 that was celebrated in 2020 and following the corporate evaluation of the National Action Plans (NAPs) to implement the WPS Agenda. xxvii The OECD’s SIGI Regional Report for Africa also highlights the important role that civil society organisations play in promoting women’s political voice, leadership and agency in Africa. xxviii

In fact, the solution to the lack of sex-disaggregated data is clear: we must bridge the representation gap. When women are involved in decision-making processes, in the production of knowledge, and in peacebuilding, they are less likely to be neglected, their rights start to truly count, and at the same time they bring a positive contribution that benefits the whole of society – even in the delicate contexts marked by armed conflicts. xxix

Bibliography

i UN Women (2022), “In Focus: War in Ukraine is a crisis for women and girls” https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/in-focus/2022/03/in-focus-war-in-ukraine-is-a-crisis-for-women-and-girls (accessed on 14 April 2022).

ii ReliefWeb (2022) “Mounting Reports of Crimes against Women, Children in Ukraine Raising ‘Red Flags’ over Potential Protection Crisis, Executive Director Tells Security Council”

https://reliefweb.int/report/ukraine/mounting-reports-crimes-against-women-children-ukraine-raising-red-flags-over (accessed on 14 April 2022).

iii GSDRC (2015), “Gender in fragile and conflict-affected environments”https://gsdrc.org/topic-guides/gender/gender-in-fragile-and-conflict-affected-environments/ (accessed on 24 March 2022).

iv EIGE (2021), “Relevance of Gender in the policy area”, https://eige.europa.eu/gender-mainstreaming/policy-areas/security (accessed on 24 March 2022).

v OECD (2021), “Gender Equality and Fragility” https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/3a93832ben.pdf?expires=1652872322&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=FF86AD098269961737FB2EC50F8D010A (accessed on 18 May 2022).

vi OECD (2019), “SIGI Global Report” https://www.genderindex.org/global-report-2019/ (accessed on 18 May 2022).

vii ECP (2021), “Alert 2021! Report on conflicts, human rights and peacebuilding” https://escolapau.uab.cat/en/publications/alert-report-on-conflicts-human-rights-and-peacebuilding-2/ (accessed on 24 March 2022).

viii OECD (2019), “SIGI Global Report” https://www.genderindex.org/global-report-2019/ (accessed on 18 May 2022).

ix IPI (2015), Marie O’Reilly, Andrea Ò Súilleabháin, and Thania Paffenholz “Reimagining Peacemaking: Women’s Roles in Peace Processes” https://www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/IPI-E-pub-Reimagining-Peacemaking.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2022).

x UN (2019), “Report on Conflict-related sexual violence” https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/report/conflict-related-sexual-violence-report-of-the-united-nations-secretary-general/2019-SG-Report.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2022).

xi IPI (2015), Marie O’Reilly, Andrea Ò Súilleabháin, and Thania Paffenholz “Reimagining Peacemaking: Women’s Roles in Peace Processes” https://www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/IPI-E-pub-Reimagining-Peacemaking.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2022).

xii UN, “Outreach Programme on the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda and the United Nations” https://www.un.org/en/preventgenocide/rwanda/ (accessed on 25 March 2022).

xiii UN (2013), “Sexual Violence: a Tool of War” https://www.un.org/en/preventgenocide/rwanda/pdf/Backgrounder%20Sexual%20Violence%202013.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2022).

xiv UNFPA (2019), “Well-Being and Safety of Women https://eeca.unfpa.org/en/publications/well-being-and-safety-women?_ga=2.8081201.220554671.1646062129-58387694.1642436549 (accessed on 18 May 2022).

xv UNFPA (2022), Ukraine: Conflict compounds the vulnerabilities of women and girls as humanitarian needs spiral” https://www.unfpa.org/ukraine-war (accessed on 18 May 2022).

xvi IPI (2015), Marie O’Reilly, Andrea Ò Súilleabháin, and Thania Paffenholz “Reimagining Peacemaking: Women’s Roles in Peace Processes” https://www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/IPI-E-pub-Reimagining-Peacemaking.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2022).

xvii QUARTZ (2016), Miriam Berger, “The radically simple way to make female refugees safer from sexual assault: decent bathrooms” https://qz.com/692711/the-radically-simple-way-to-make-female-refugees-safer-from-sexual-assault-decent-bathrooms/ (accessed on 19 May 2022).

xviii Criado Perez, C., “Invisible Women”, Einaudi, 2020.

xix EMWF (2021), “Gender and Conflict Analysis toolkit for peacebuilders” https://www.euromedwomen.foundation/pg/en/documents/view/9610/gender-and-conflict-analysis-toolkit-for-peacebuilders (accessed on 29 March 2022).

xx European Parliament (2021), “Women in foreign affairs and international security” https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/689356/EPRS_BRI(2021)689356_EN.pdf (accesses on 29 March 2022).

xxi CFR (2019), Women’s participation in peace processes, https://www.cfr.org/womens-participation-in-peace-processes/ (accessed on 25 March 2022).

xxii IPI (2015), Marie O’Reilly, Andrea Ò Súilleabháin, and Thania Paffenholz “Reimagining Peacemaking: Women’s Roles in Peace Processes” https://www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/IPI-E-pub-Reimagining-Peacemaking.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2022).

xxiii UN Women (2021), “Facts and figures: Women, peace, and security” https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/peace-and-security/facts-and-figures#:~:text=Between%201992%20and%202019%2C%20women,or%20women%20signatories%20%5B22%5D. (accessed on 18 May 2022).

xxiv NOREF (2016), Clare Castillejo “Women Political Leaders” https://noref.no/Publications/Themes/Peacebuilding-and-mediation/Women-political-leaders-and-peacebuilding (accessed on 19 May 2022).

xxv OECD (2020), “States of Fragility” http://www3.compareyourcountry.org/states-of-fragility/about/0/ (accessed on 19 May 2022).

xxvi European Parliament (2020), “Resolution on Gender Equality in EU’s foreign and security policy” https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0286_EN.html (accessed on 29 March 2022).

xxvii OECD (2021), “Gender Equality and Fragility” https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/3a93832ben.pdf?expires=1652872322&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=FF86AD098269961737FB2EC50F8D010A (accessed on 18 May 2022).

xxviii OECD (2021), “SIGI 2021 Regional Report for Africa » https://www.oecd.org/dev/sigi-2021-regional-report-for-africa-a6d95d90-en.htm (accessed on 19 May 2022).

xxix Criado Perez, C., “Invisible Women”, Einaudi, 2020.