Female out-migration from Thailand

Introduction

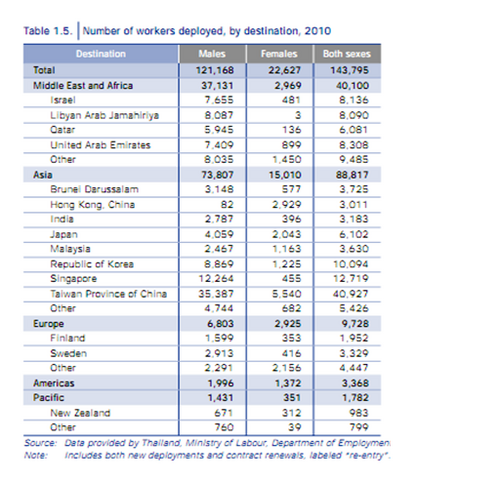

The movement of people searching for a better life is a reality in many countries around the world, whether it is for economic reasons, political reasons or to escape from natural disasters. People migrate within their own countries, mainly from rural to urban areas, but also across borders. Thailand has, through official channels, deployed approximately 150,000 migrant workers a year since 1999. The number of migrants in 2010 was 143,795 (see table 1.5 below, of which 62% went to economies in Asia and 28% went to the Middle East and Africa;only 16% of the migrant workers were women. This article specifically looks at the economic, social and environmental determinants (or push factors) of female migration from Thailand.

Economic factors

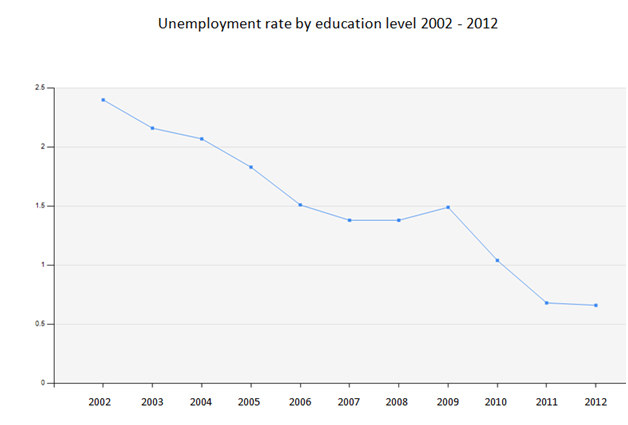

Although economic factors are not always the main reason, it is one of the most important reasons behind female migration from Thailand. Thai women seek to emigrate in order to escape from situations of unemployment, poverty, low wages or limited economic opportunities. Poverty and inequality between men and women as well as the access to information are powerful factors influencing the decision for women to migrate. Figure 1 shows the poverty headcount as a percentage of population, which is quite high compared to developed countries. Poverty could lead to more intense problems such as the difficulty to afford educational fees, especially for women. Figure 1: Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty line (% of population)Source : World Bank, Global Poverty Working Group. Data are based on World Bank’s country poverty assessments and country Poverty Reduction Strategies.  Note – National poverty rate is the percentage of the population living below the national poverty line. National estimates are based on population-weighted subgroup estimates from household surveys. Figure 2 shows the unemployment rate by education level in Thailand. The unemployment rate was high in 2002 and then gradually decreased between 2002 and 2009. From 2009 to 2011, the unemployment rate decreased rapidly and there was a slight decrease between 2011 and 2012. Figure 2: unemployment rate by education level in Thailand. Unemployment rate high at 2002.Source : National Statistical Office Thailand

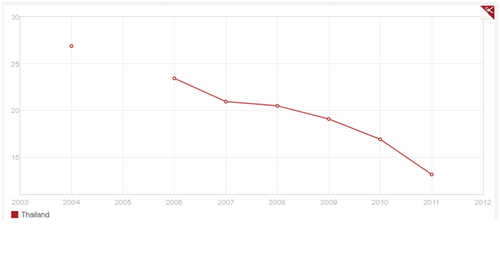

Note – National poverty rate is the percentage of the population living below the national poverty line. National estimates are based on population-weighted subgroup estimates from household surveys. Figure 2 shows the unemployment rate by education level in Thailand. The unemployment rate was high in 2002 and then gradually decreased between 2002 and 2009. From 2009 to 2011, the unemployment rate decreased rapidly and there was a slight decrease between 2011 and 2012. Figure 2: unemployment rate by education level in Thailand. Unemployment rate high at 2002.Source : National Statistical Office Thailand  Note: Average unemployment in 10 year In many countries, women face discrimination and even gender-based violence. They are also paid significantly less than men for doing the same type of work. Also, the work deemed suitable for women usually attracts lower salaries than work suitable for men. In addition, the domestic work that women are mostly required to conduct in their ‘spare time’ is unpaid. Figure 3 shows that the unemployment of Thai women is not a significant factor in international migration from Thailand: the unemployment rate is quite low in Thailand and women have lower unemployment rates in comparison to men. Figure 3: Unemployment rate of male and female in the labor force in Thailand between 2004 – 2013(1st quarter) Unemployment Rate,National Statistical office, Ministry of Information and Communication Technology, Thailand

Note: Average unemployment in 10 year In many countries, women face discrimination and even gender-based violence. They are also paid significantly less than men for doing the same type of work. Also, the work deemed suitable for women usually attracts lower salaries than work suitable for men. In addition, the domestic work that women are mostly required to conduct in their ‘spare time’ is unpaid. Figure 3 shows that the unemployment of Thai women is not a significant factor in international migration from Thailand: the unemployment rate is quite low in Thailand and women have lower unemployment rates in comparison to men. Figure 3: Unemployment rate of male and female in the labor force in Thailand between 2004 – 2013(1st quarter) Unemployment Rate,National Statistical office, Ministry of Information and Communication Technology, Thailand  Figure 4 indicates that there are more employed men than women, which suggests that there may be some obstacles for women to get a job, such as discrimination in the labour market or restrictions that favour men. Figure 4: Employee (per 1,000 person) in Thailand between 2004 – 2013Employee (per 1,000 person) in Thailand between 2004 – 2013, National Statistical office, Ministry of Information and Communication Technology, Thailand

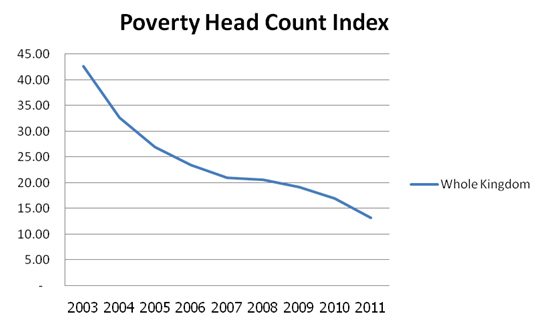

Figure 4 indicates that there are more employed men than women, which suggests that there may be some obstacles for women to get a job, such as discrimination in the labour market or restrictions that favour men. Figure 4: Employee (per 1,000 person) in Thailand between 2004 – 2013Employee (per 1,000 person) in Thailand between 2004 – 2013, National Statistical office, Ministry of Information and Communication Technology, Thailand _in_Thailand_between_2004_-_2013.jpg) Finally, in Figure 5 we can see that the poverty head count index also shows that poverty in Thailand is sharply decreasing. Therefore, determinants for female emigration from Thailand may be caused by other factors such as higher wages relative to those in Thailand, more economic opportunities, etc. If compared to the same characteristics in terms of wages or salary received while working in the country, there may be an incentive for workers to move abroad, seeking a better quality of life in terms of salary. Figure 5: Head Count Index, Thailand between 2003 – 2011Head Count Index, Thailand between 2003 – 2011, National Statistical office, Ministry of Information and Communication Technology, Thailand

Finally, in Figure 5 we can see that the poverty head count index also shows that poverty in Thailand is sharply decreasing. Therefore, determinants for female emigration from Thailand may be caused by other factors such as higher wages relative to those in Thailand, more economic opportunities, etc. If compared to the same characteristics in terms of wages or salary received while working in the country, there may be an incentive for workers to move abroad, seeking a better quality of life in terms of salary. Figure 5: Head Count Index, Thailand between 2003 – 2011Head Count Index, Thailand between 2003 – 2011, National Statistical office, Ministry of Information and Communication Technology, Thailand

Social and Environmental factors

Female migration is also motivated by social factors, including surveillance by communities and patriarchal traditions that limit opportunity and freedom, getting out of a bad and abusive marriage, fleeing from domestic violence and desiring equal opportunities. In particular, factors that may contribute significantly to the decision to migrate include familial obligations as well as limited social opportunities. For example, discrimination against certain groups of women (such as single mothers, unmarried women, widows or divorced women) drives many women to migrate. However, a significant number of women still migrate as wives because in many countries, in the case of domestic violence, they risk losing their residence rights if they decide to leave their spouses. Migration processes with a gender fccus should be closely scrutinised in order to prevent hidden risks and promote new opportunities for women and their families. Thai women’s decision to migrate depend on many factors: discrimination and exclusion, unfavourable legislation, risks, the impact on those “left behind” (such as children or the elderly), etc. The level of inequality between men and women in decision-making processes are powerful forces influencing female migration. For example, when women get married young, they receive little and poor-quality education, bear many children at a young age, lack access to credit and banking and have very few rights. They therefore lack the decision-making capacity and necessary resources to migrate. Another factor that can cause migration is the occurence of natural disasters. Thailand is one of the many countries in the world with a tropical climate. Monsoons happen regularly during the rainy months, so floods are common throughout Thailand. In the rural areas, people suffer from floods in the rainy season and drought in the summer due to insufficient infrastructure. People in the rural areas use insecurity as a reason to migrate to safer places, both in the country and abroad. Even though natural disasters occur around the world, developed countries such as the and Japan have early-warning systems, education and safety campaigns as well as assistance programmes before and in the aftermath of a disaster.

Threats and opportunities for female migration

Opportunities

Migration can contribute to gender equality and female empowerment by providing migrant women with income, status, autonomy, freedom and the self-esteem that comes with employment. Women become more assertive as they see more opportunities opening up before them. Relocating to a new country exposes women to new ideas and social norms that can promote their rights and enable them to participate more fully in society. It can also have a positive influence on achieving greater equality in their country of origin, through the transmission of ideas. In societies where migration increases contact between different countries and their inhabitants, new existential challenges and transcultural dialogue between different groups and subgroups gains more importance. Given the formative role that women play in countries of destination and their important role in formative child care, they have a great influence on the openness of new generations to other cultures — especially considering the kind of relationships they establish with the local population and with other migrants.

Challenges

On the other hand, women from poor environments who have experienced lack of opportunities and violence are likely to become easy targets for traffickers, who promise them a richer economic and social future abroad whilst luring them into forced labour (such as prostitution, sweat-shops and poor domestic work conditions). In this case, prevention efforts such as providing information on the possible risks before, during and post-migration and how to avoid them, are vitally important.

Conclusion

Female international migration might affect Thailand in various aspects. First economically, Thailand may face a lack of labour due to women’s migration as they search for economic opportunities and higher wages compared to what they would have in Thailand. Women want to migrate to achieve a better life with new opportunities, increased income and higher social status. Second, female migration also affects Thailand socially: most families are unable to take their children with them due to overly restrictive migration policies and the high costs of international migration. This would lead to negative behaviour of their children, as women who leave their families fail to provide love and care most needed in their formative care. It has also been proven that children with parents who have not migrated obtain better qualifications than those whose parents are abroad.

References

- http://www.caritas.org/ (7th March 2012), Female face of migration, http://www.caritas.org/includes/pdf/backgroundmigration.pdf

- http://www.policy.doe.go.th/ebook/020400004399_2.doc , Planning and Information Division, Department of employment, Ministry of labour, literature review, 020400004399_2.doc

See also

Group 1

From left to right: Mr. Tanakorn Chaianekwut, Mr. Jirayut Songkrampoo, Miss Chulalak Kongsook, Miss Preeyaporn Eakthanyawong, Mr. Burakarn Tippayasakulcahi, Mr. Supanut Sawetarpa