The SOFA Report 2011: “Women in agriculture: Closing the gender gap for development”

This report documents the different roles played by women in rural areas of developing countries and provides solid empirical evidence on the gender gaps they face in agriculture and rural employment.

Table of Contents

- 1 About the report

- 2 Selected data and figures

- 3 Experts’ event on 8 March 2011

- 4 Join the online discussion

- 5 Access the report

- 6 See also

About the report

Agriculture is central to food security and global economic growth. In the last decade, governments and donors have made major commitments to revitalize the sector in developing regions. Yet, despite being more technologically sophisticated, commercially oriented and globally integrated, it is still underperforming. One of the key reasons is that the productivity of women in developing regions is stunted by a lack of access to resources and opportunities.

Women make sizable contributions to agriculture and other rural enterprises as farmers, workers and entrepreneurs. They make up 43 percent of the agricultural labour force of developing countries, from about 20 percent in the Americas to almost 50 percent in East and Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. While their roles vary across regions, one factor remains constant: everywhere, women face constraints that limit their capacity to contribute to agricultural production. They are also more likely to be in part-time, seasonal and/or low-paying jobs when engaged in wage employment. These factors not only affect their welfare and that of their families, but also impose a high cost on the economy and diminish the world’s capacity to achieve the first Millennium Development Goals#Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger (MDG1)–global food security.

The Gender Gap in access to assets is largely dictated by Social institutions and extends to all dimensions of agriculture. Customary practices often restrict women’s ability to own or operate Access to land, the most important asset for households that depend on agriculture. Women hold between 10 and 20 percent of total land in developing countries, generally of a lesser quality than men’s. They own fewer of the working animals needed in farming, like horses and cattle, and do not always have control over income from the typically small animals they manage, such as goats, sheep, pigs and poultry.

Women also have less Access to Education, which is strongly linked to the productive capacity of households, and to financial services such as credit. These factors hamper their capacity to adopt new technologies, invest in equipment and inputs liked fertilizers and improved seeds, take advantage of extension services and participate in modern high value agricultural activities.

The gender gap is manifest in other ways. Women are traditionally responsible for household obligations such as collecting water and fuel, working on household plots, processing and preparing food and maintaining the house. With scant availability of labour-saving technologies like water pumps and grain mills, these responsibilities significantly limit the time women can spend on productive activities.

As a result of these combined constraints, women farmers’ yield is on average 20 to 30 percent lower than men farmers’ in developing countries. Ample evidence confirms that women are as good at farming as men and that these results are entirely due to the gap in access to productive inputs. If women were empowered to produce the same yields as men, agricultural output in developing countries would increase by 2.5 to 4 percent.

There are 925 million undernourished people in the world today. Productions gains of this magnitude could reduce the number of hungry by 12 to 17 percent – 100 to 150 million people – a significant progress towards achieving MDG1.

This would be one of many beneficial outcomes. With more control over resources and income, women would achieve greater influence over economic decisions – a proven strategy to increase household investment in children’s nutrition, health and education, which in turn improves human capital, economic growth and prosperity for all in the long run.

There is no blueprint for closing the gap in agriculture and rural employment, but some basic principles are universal: governments, the international community, civil society and the private sector can work together to eliminate discrimination against women under the law, strengthen investments in labour-saving technologies and public services to alleviate their household burden, build up rural institutions and make them gender-aware, strengthen the human capital of women and girls, improve the collection and analysis of sex-disaggregated data, ensure that agricultural policies and programmes are gender-aware, and make women’s voices heard as equal partners for sustainable development.

Achieving gender equality and empowering women in agriculture is the right thing to do – for women and for the future of global food security.

Selected data and figures

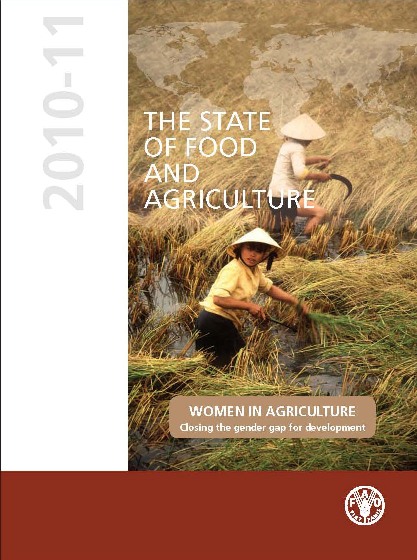

Figure 1: Female share of the agricultural labour force

Based on the latest internationally comparable data, women comprise an average of 43 percent of the agricultural labour force of developing countries. The female share of the agricultural labour force ranges from about 20 percent in Latin America to almost 50 percent in Eastern and Southeastern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. The regional averages in Figure 1 mask wide variations within and among countries. For further details, see Annex tables A3 and A4 of the SOFA report.

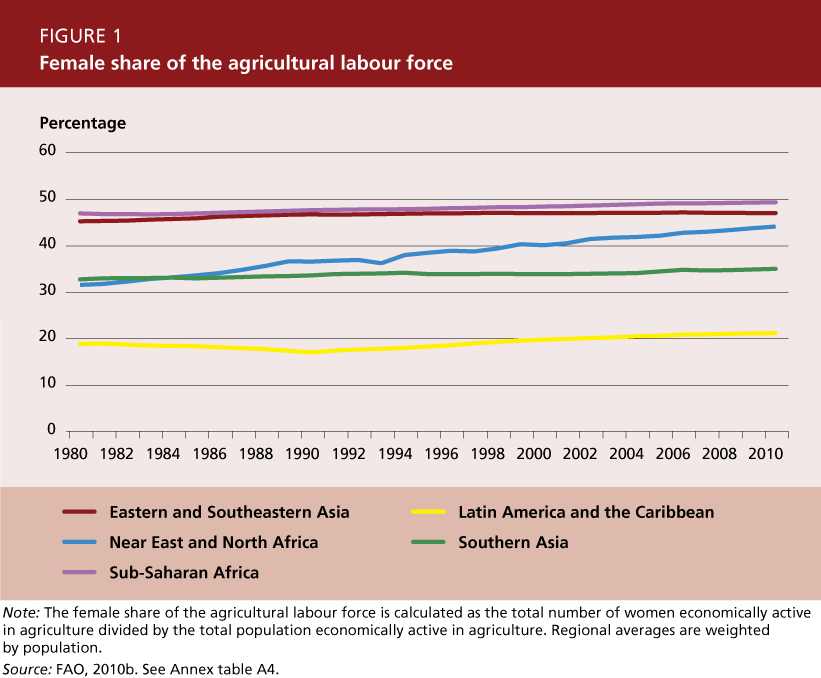

Figure 4: Employment by sector

Figure 4A

About 70 percent of men and 40 percent of women in developing countries are employed. Male employment rates range from more than 60 percent in the Near East and North Africa to almost 80 percent in sub-Saharan African. Female employment rates vary more widely across regions, from about 15 percent in the Near East and North Africa to over 60 percent in sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 4B

In Asia and in sub-Saharan Africa, women who are employed are more likely to be employed in agriculture than in other sectors. Almost 70 percent of employed women in Southern Asia and more than 60 percent of employed women in sub-Saharan Africa work in agriculture. In most developing country regions, women who are employed are just as likely, or even more likely, than men to be in agriculture. The major exception is Latin America, where agriculture provides a relatively small source of female employment and women are less likely than men to work in the sector.

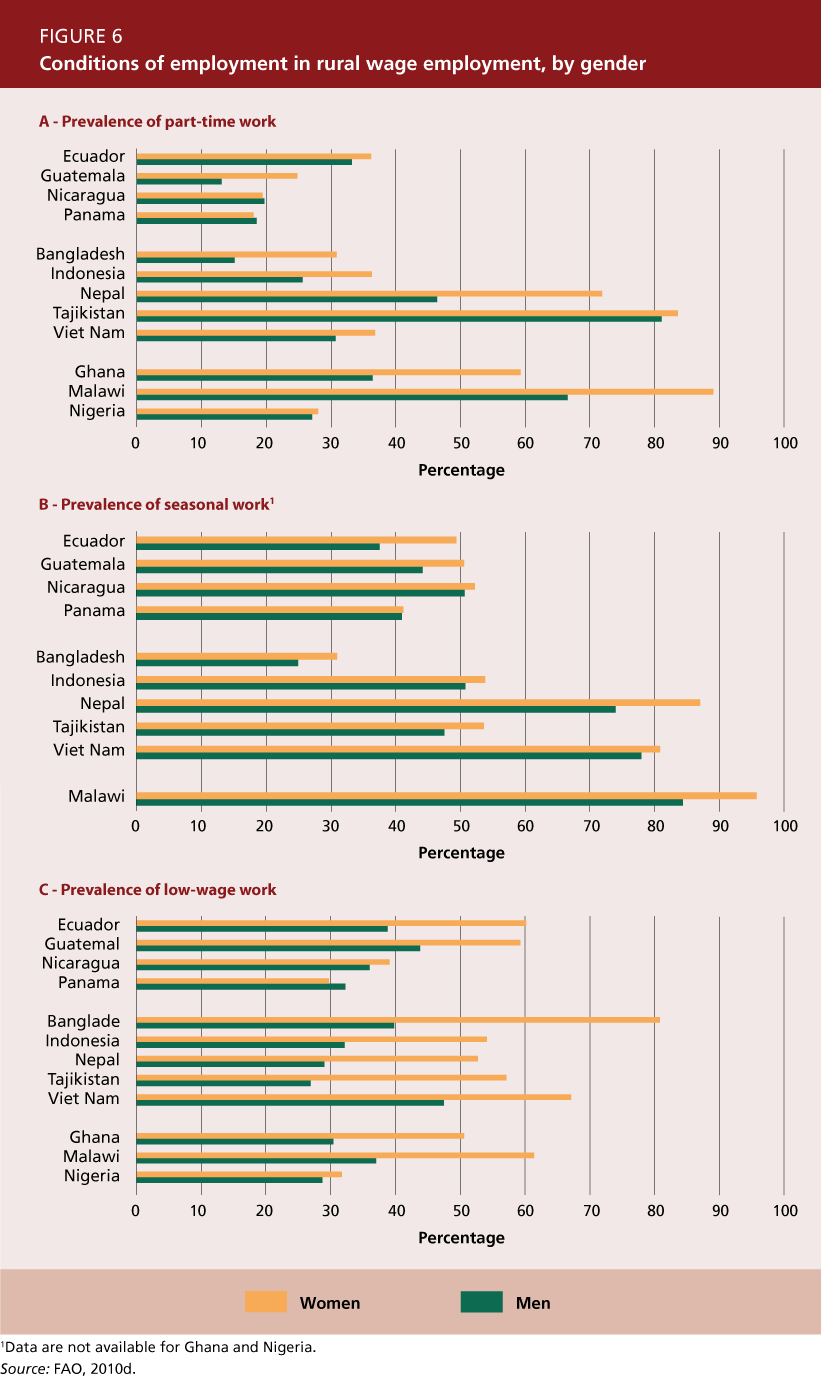

Figure 6: Conditions of employment in rural wage employment, by gender

Figure 6A

Even when rural women are in wage employment, they are more likely to be in part-time, seasonal and/or low-paying jobs. In Malawi, for example, 90 percent of women and 66 percent of men work part-time. In Nepal, 70 percent of women and 45 percent of men work part-time. This pattern is less pronounced in Latin America than in other regions.

Figure 6B

Rural wage employment is characterized by a high prevalence of seasonal jobs for both men and women, but in most countries women are more likely than men to be employed seasonally. For example, in Ecuador, almost 50 percent of women but fewer than 40 percent of men hold seasonal jobs.

Figure 6C

Similarly, rural wage-earning women are more likely than men to hold low-wage jobs, defined as paying less than the median agricultural wage. In Malawi, more than 60 percent of women are in low-wage jobs compared with fewer than 40 percent of men. The gap is even wider in Bangladesh, where 80 percent of women and 40 percent of men have low-wage jobs. The only exception to this pattern was found in Panama.

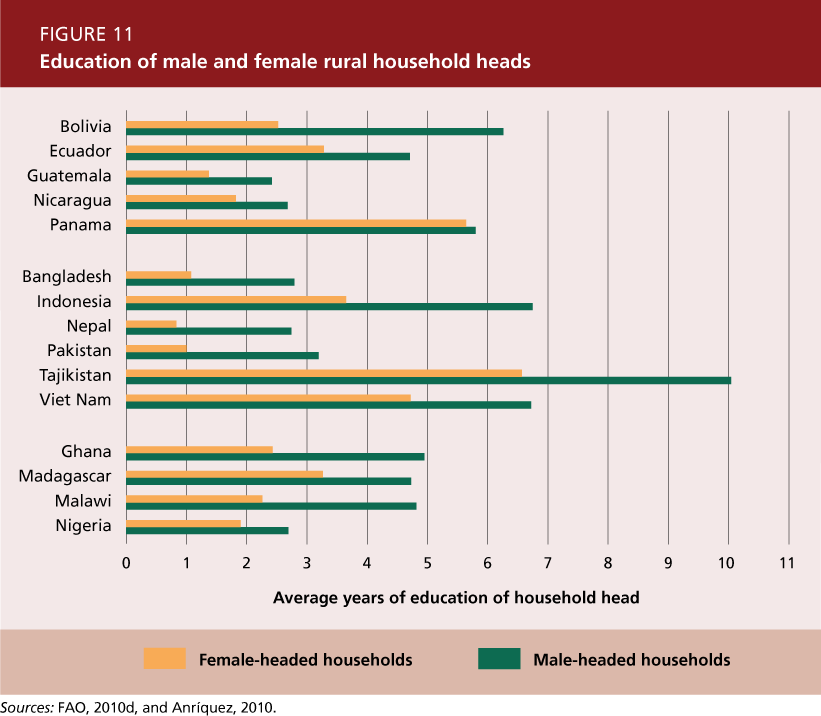

Figure 11: Education of male and female rural household heads

Gender differences in education are significant and widespread. Female heads have less education than their male counterparts in all countries in the sample except Panama, where the difference is not statistically significant. The data suggest that female household heads in rural areas are disadvantaged with respect to human capital accumulation in most developing countries, regardless of region or level of economic development.

Gender differences in education are significant and widespread. Female heads have less education than their male counterparts in all countries in the sample except Panama, where the difference is not statistically significant. The data suggest that female household heads in rural areas are disadvantaged with respect to human capital accumulation in most developing countries, regardless of region or level of economic development.

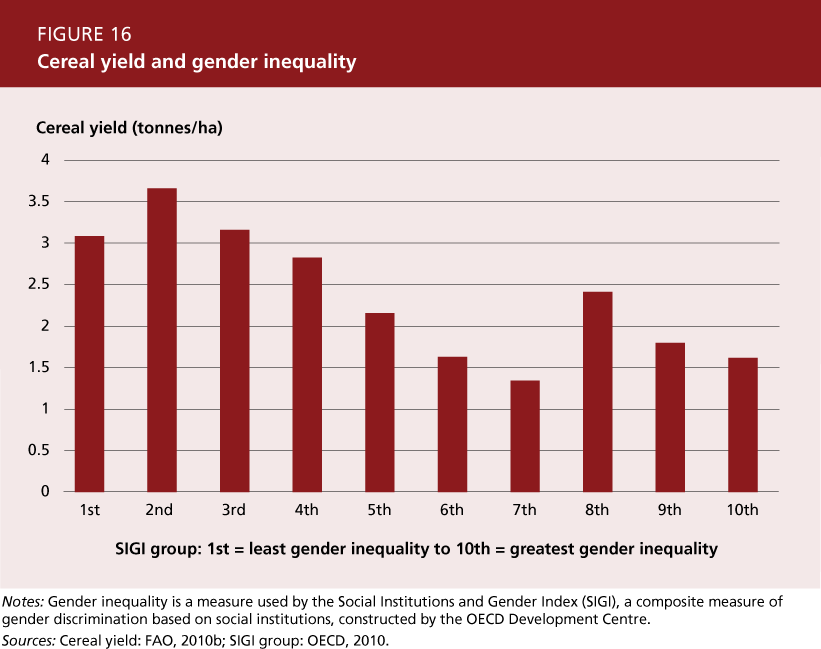

Figure 16: Cereal yield and gender inequality

The relationship between gender equality and agricultural productivity can be explored using Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ’s 2009 Social Institutions and Gender Index (OECD, 2010). The SIGI index reflects social and legal norms such as property rights, marital practices and civil liberties that affect women’s economic development. A lower SIGI indicates lower levels of gender based discrimination. Countries with lower levels of gender inequality tend to achieve higher average cereal yields than countries with higher levels of inequality. Of course, the relationship shows only correlation, not causation, and the direction of causality could run in either direction (or in both directions). In other words, more equal societies tend to have more productive agriculture, and more productive agriculture can help reduce gender inequality.

Experts’ event on 8 March 2011

A debate organized by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (International Fund for Agricultural Development) and the World Food Programme (WFP), was held on March 8, International Women’s Day, focussing on the key messages and policy recommendations from the FAO’s State of Food and Agriculture Report 2010-11.

The participating experts discussed the costs of gender inequality for agricultural productivity, poverty and hunger and discussed appropriate action to be taken.

It was streamed live online at 8:30-11:30 GMT (9:30-12:30 CET):

You can access the programme of the event.

Online discussion

Women in agriculture and food security: How can we turn rhetoric into reality? was an open online debate organized by FAO’s Global Forum on Food Security and Nutrition to enrich the discussion around the report. Visitors were encouraged to share their views and experience on policies that have worked or failed to achieve gender equality in agriculture, their consequences and how to promote the design and implementation of agricultural policies that are gender-aware and gender-transformative; programmes and projects that have proved particularly innovative and catalytic for enhancing rural women’s agricultural roles, output and livelihoods; and supporting poor rural women in their efforts to mobilize and empower themselves.

To read more about the debate, click Discussion: %22Women in agriculture and food security: How can we turn rhetoric into reality%3F%22.

Access the report

- To access the full report, visit the SOFA Webpage.

- For more information, visit FAO’s gender website

See also

- FAO

- Women and Agriculture

- Women and Women and African Economic Developmentn Economic Development

- Access to land

- Women and Land Tenure

- 2009 2009 Social Institutions and Gender Index