Ciudad Juárez: ‘Feminicidios’ and sexual violence

Since 1993, close to 400 women have been found murderd in the Mexico city of Ciudad Juárez, close to the Gender Equality in the Gender Equality in the United States of America of America of America border.  The criminal phenomenon is called in Spanish the feminicidios (“femicides”) or las muertas de Juárez (“The dead women of Juárez”). Most of the cases remain unsolved.

The criminal phenomenon is called in Spanish the feminicidios (“femicides”) or las muertas de Juárez (“The dead women of Juárez”). Most of the cases remain unsolved.

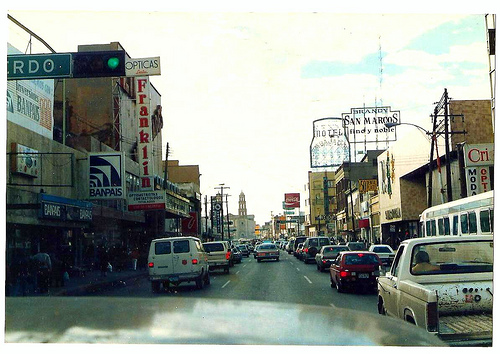

Ciudad Juárez is a city of 1.5 million that has become a battleground for drug cartels. More than 1,550 people were killed there in drug wars in 2008. In 1993, 25 women were found murdered with their dumped bodies showing clear signs of Sexual violence, torture and Rape . In 1995, 42 women’s bodies were found, most of them showing signs of sexual violence – including of girls as young as 12 and 13.

Feminicidios

In 2003 Amnesty International issued a report, Intolerable Killings: 10 years of abductions and murders of women in Ciudad Juarez and Chihuahua highlighting the pattern of killings and abductions of women in Ciudad Juárez and the City of Chihuahua. The report found that in 2003, over 370 women had been murdered, and at least 137 of them after being sexually assaulted . In addition, over 70 young women were still missing, according to the authorities, though Mexican non-governmental organizations say the figure is over 400.

The women murdered are usually young women, 16-20 years old on average (though a 12 year old girl’s body was also found), from poor backgrounds. The pattern of sexual violence includes abduction, captivity for serveral days, vicious sexual assault, and murder before the body is dumped in rubble on wasteland. In some cases, their remains are found by passersby days or even years later. In other cases, the women are never found.

According to Amnesty International, evidence seems to indicate that these young women are chosen by their killers because they are women who have no power within Chihuahuan society. The women are usually workers from the maquiladoras set up by the multinational companies that control the economy of Ciudad Juárez as well as waitresses, workers in the informal economy or students. Many of them live in poverty, often with children to support. They are women who have no option but to travel alone on the long bus journeys that take them from the poor suburbs surrounding Ciudad Juárez to their place of work, study or leisure.

Political Reaction

The response of the authorities over the past ten years has been to treat the different offences as ordinary acts of violence committed within the private domain, without recognizing the existence of a continuing pattern of violence against women. When families have reported their female relative missing, authorities wait many days before acting despite the trend of kidnappings, sexual violence and murder. In 2005, the Governor of the state of Chihuahua said that international attention on the situation in Ciudad Juarez is damaging the city’s public image.

In 2005, judges in Mexico found 10 members of two criminal gangs who were already behind bars guilty over the killings of 12 women in Ciudad Juarez. They were sentenced to between 40 and 113 years for premeditated homicide, aggravated rape and criminal association in the killings of six women.

International Condemnation

The Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Women of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), Marta Altolaguirre, highlighted the high level of discrimination against women that influenced authorities’ actions in her March 2003 report. She pointed out that, in 1993, when the crimes exhibiting a specific pattern began, the authorities repeatedly blamed the women themselves for their own abduction or murder and refused to acknowledge that the situation was out of the ordinary. Since the girls were poor and young, they were seen as “expendable”.

Amnesty International has attacked the systemic failures in the Mexican authorities’ treatment and approach to the murders, criticising also the convictions. “The lack of proper investigations has led authorities to resort to torture to extract confessions where evidence is not available. This has not only led to the imprisonment of individuals who may be innocent, but also means that there is a strong likelihood that the real perpetrators are escaping justice and are free to continue to commit crimes.”

Media Attention

- In 2001, filmmaker Lourdes Portillo released one of the first documentaries dedicated to the victims of the murders, Señorita Extraviada.

- In 2002, U.S. border journalist Diana Washington Valdez published an investigative newspaper series in the El Paso Times about the murders titled “Death Stalks the Border.”

- In the same year Polish journalists Eliza Kowalewska and Grzegorz Madej released a TV series about crimes in Juárez.[10] Journalists cooperated with crime experts Robert Ressler and Candice Skrapec. This series was shown on Polish television TVN in 2003.

- In 2006, Los Angeles filmmaker Lorena Mendez produced Border Echoes, a documentary about the Juárez women’s murders based on nearly 10 years of investigation.

- In 2006, Gregory Nava directed a movie called Bordertown with Jennifer Lopez and Antonio Banderas.

References

- La Cite des Mortes

- International, “Intolerable Killings” (2003)

- NY times news article

- Wikipedia Page

- Guardian news article